How can we help pupils succeed at independent historical enquiry, without them getting lost enroute?

How can we help pupils succeed at independent historical enquiry, without them getting lost enroute?

Some scene setting: Meeting Mr Gove and brandishing a candlestick

A few years ago I was lucky enough to attend a conference called ‘The Future of the Past’. It was held in a big ‘Mr-White-with-the-candlestick-in-the-dining-room’ type manor house, and was funded by a philanthropist called Lord Weidenfeld. It included a collection of about 25 people sitting around a big table in the library – including history teachers, historians, university lecturers, education policy-makers from other countries, TV producers…and Michael Gove, who was Education Secretary at the time. Civil servants sat around the outside in dark suits, listening in. I have vivid memories of Simon Schama, energetically chairing some of the discussions, his red scarf and expressive arms waving riotously, and of him sitting sprawled on a chaise longue at the back of the drawing room during the plenary session, muttering into his mint tea.

Jung Chang came for dinner.

The major discussions: from the merits of the Albanian education system to empire guilt

Many things were discussed. How ‘amazing’ it was that England is the only country in Europe not to ask its pupils to study history until age 16 (even Albania has now seen the light). The 70% of British children who don’t go on to study history at GCSE; what should the first two or three years give them in terms of a grounding in historical education? How might an ‘historical awareness’ by secured for these pupils? Thoughts on the value of history in developing pupils’ literacy skills. Reflections on the new ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ (which I considered, at the time, to be a buzzword and a euphemism for Gove’s first draft of an unwieldy, pro-British curriculum that attempted to teach pupils everything that had ever happened in, for example, the long eighteenth century).

What else? The importance of ‘hooks’ and ‘telling stories’ through the effective delivery of historical knowledge, all the while balancing strangeness and familiarity. The use of audio-visual material to help tell those stories. Getting the balance between local, British and world history right. The importance of the inter-connectedness of local, national and world history, for example through the creation of parallel timelines, and through the use of ‘micro-narratives’ such as Eamon Duffey’s ‘Voices of Morebath’, which could be situated within wider, national developments (in this case, developments in the Reformation). The fact that pupils from diverse backgrounds are not impressed by ‘disconnected diversity’ – their stories need to be connected to wider national and international historical narratives. The lack of time to deliver a comprehensive grounding in British/world history due to pressure on results. How will pupils be able to develop a ‘big picture’ of the past, or engage with historical concepts meaningfully, if they are taught history for one term a year, as they are in some schools?

Fundamentally, the role of history in promoting citizenship was discussed– including the fostering of historical awareness and how to use the internet intelligently. Also, the centrality of the second-order concept of interpretations in the new curriculum was emphasised. In discussion with education policy-makers, university lecturers and students from America, Germany, Poland, Brazil and Russia, it appeared that the UK is uniquely self-conscious and self-critical in its continued resistance to the use of history to promote a certain identity. In other countries, history is used to promote a certain identity, patriotism and pride in the past. Some of the conference members were keen that whilst Britain should move on from ‘empire guilt’ (and, indeed, move on from the idea that teaching British History is dangerously partisan), Britain’s strength in terms of its historical education is the teaching of multiple narratives. This ensures that pupils can recognise that there is more than one way of looking at historical events. How can we ensure that all student-teachers are trained to teach the important concept of interpretations, especially with PGCE providers suffering from lack of funding and resources?

Why Simon Schama made me change our Year 9 Scheme of Work

A final discussion thread that fascinated me were problems encountered by history professors teaching at university level. The professors present at the conference (including Simon Schama from Columbia University and Christopher Clark from the University of Cambridge, the latter suffering from a heavy cold due to all of his World War I centenary commitments) mentioned that pupils often arrive at universities woefully unprepared for independent study – mainly due to the fact that exam demands leave little room for independent learning.

It was this lack of preparation for independent study that I wanted to respond to first, when I walked into the history department office after attending the conference (and after having responded to the ubiquitous ‘what-was-Gove-like-did-you-speak-to-him?’ questions.) Due to the usual issues of time constraints and pressure on results, it was not possible to construct a scheme of work at GCSE or A-Level in independent learning.So we opted to work on helping students to get better at independent enquiry during Year 9, drawing from these skills in later years and reminding pupils in examination classes what they had learnt. The study of events in 1945-2010 was extremely popular, and we felt that this was a suitable time period for pupils to choose a topic from, considering that, for example, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the achievements of Nelson Mandela, the Swinging Sixties and the Troubles in Ireland were all topics that the students would have heard about – and would hopefully have the passion to study over an extended period of time.

This became my first principle for constructing a scheme of work for independent learning. Help pupils to find a topic that will interest them enough to ‘stay the course’ in terms of extensive research. This involved pupils choosing their topic, but also guiding them in terms of providing a selection of topics that would excite them, and which would lead to a rigorous enquiry. This meant steering them away from vague notions of researching ‘stuff that happened with terrorists’, and towards specific events and actions that were time-bound, and would therefore be practically researchable within the seven-lesson enquiry. Our final decisions about which topics pupils could choose from are on page 2 of the resulting booklet (find it here: Year 9 Summer Project Booklet).

Designing a scheme of work to promote independent learning about the past – practical lessons learnt

A second principle that reared its ugly head (because it hadn’t been dealt with properly in our first trial of the scheme of work) was ensuring that adequate resources are available on all topics that are made available for the students to study. During the trial, I let students have a ‘free rein’ on their selection of which topic to research, and then sent them,with a big smile on my face and an open sweep of my hand as if to say ‘Go! Be free! For all this is yours! Discover the delights instore!’, into the school library.

Of course this meant that Johnny’s group immediately went to the furthest corner of the library, flirted with each other outrageously, and sent Tom (‘the responsible one’) to desperately try to find some books that were vaguely related to the Vietnam War. Every time I went over, their response was ‘there-isn’t-anything-there-plus-Tom-is-still-looking’. Meanwhile, Tom was locked in a tug-of-war over the only book that was relevant to the Vietnam War (three groups having chosen this topic, apparently fascinated by the ‘napalm and stuff’). In the middle of the room, having quickly decided that there were, in fact, no relevant books on the Chernobyl disaster other than a dusty encyclopedia, another group were on laptops researching the topic online. All three were using Wikipedia.

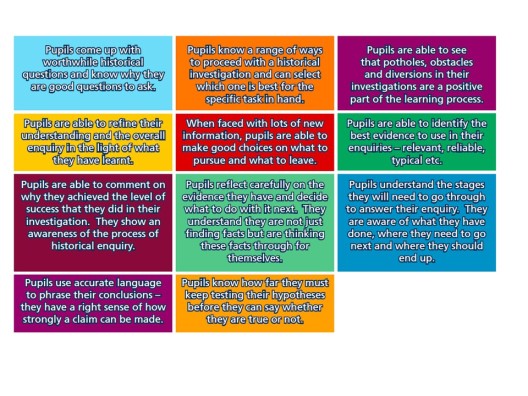

What had gone wrong? Several things, if I’m honest. Part of the problem is that I hadn’t identified and attempted to resolve the practical issues that students might come across. I handn’t prepared properly. Luckily, unlike my students, I knew where to look to improve my knowledge about pupil-led enquiry. Kate Hammond has written about what an effective pupil-led enquiry might look like in Teaching History, identifying eleven attributes that might be seen in a pupil successfully undertaking an historical enquiry:

Not only did I learn much from Hammond’s excellent article; several lessons were quickly learnt by my rather unproductive trip to the library:

- Liaise with the librarian(s). Ask them to come up with a reading list, to help you identify how many books there are to support research on each topic and, more importantly, how relevant, detailed, accessible, and dated each book is. Update this every year, and ask the librarian to order in (if possible, and budgets allow, perhaps on loan) extra books so that every topic is adequately supported by books. After all, at university, history students are given a reading list before being set an essay question. Why ask a thirteen year old to do something that has already been done for a nineteen year old? Making it easy to find appropriate books means more time for the students to be note-taking, highlighting and arranging their ideas.

- Think about having groups do different topics within a single class. This idea really divided the department, and we still can’t agree. On the one hand, allowing more than one group to do a topic will ensure that students have chosen their absolute favourite, and therefore will hopefully be committed and more invested in the research process. On the other hand, as happened last year, this can lead to the situation where half of each class want the same books, and you end up with 6 presentations in a row on 9-11 or Al Qaeda (or something in between). Therefore, another idea is to allow students to ‘bid’ for a topic, and once they have secured it, no one else in the class can do that topic. This should create a wider variety of topics. We had different ideas for how students could bid for topics- picked at random (for example drawn out of a hat); based on assessment performance; based on scores in a 1945-2010 quiz, and so on. The issue is that students may not end up studying what they really wanted to study – and so may be less passionate about the research. And students need to maintain interest across the 6-7 lessons we allowed.

- Keep the books from the reading list in the library. A very simple arrangement which ensures that students can access books during class time and after school.

- Provide manageable deadlines for students to work to. I like to ask pupils to, for example, ‘have noted 8 or more facts about the topic in every booklet by the next lesson’. The deadlines are written down on the front page of every pupil’s booklet. I then mention when the next lesson is, for the very disorganised. This helps in two ways: first, it reminds pupils that the project is a team effort (I also have a list of teamwork skills within the booklet), with everyone making notes rather than just one workhorse and two magpies; and second, it means that pupils do not sit around (‘please stop flirting, Johnny’) thinking they have all of the time in the world. Until they don’t. At which point they give up, because they have too much to do. Which leads me on to…

- Give constant reminders about when the final presentation is due. This avoids a mad rush at the end or – worse – a project that falls flat on its face.

- Help pupils to think about the advantages and disadvantages of different types of resources. What are the advantages of using the library? What are the potential disadvantages. Steer them away from Wikipedia, reminding them why Wikipedia is so unhelpful, and provide some alternatives, such as the National Archives online.

- Demonstrate different ways of locating and organising information, such as skimming and scanning, using tables and colours to organise notes. Remind them to keep their notes together – or, even better (and if budgets allow), create a booklet for them, like my Year 9 Summer Project Booklet.

- Show pupils examples of effective handouts and/or presentations created by successful groups in previous years. You could also remind them what is not a good presentation. For example:

9. Present students with some research scenarios in which something has gone wrong. And then ask them to correct them. For example:

10. Provide a list of assessment criteria for students to work to. By stating that pupils will be peer assessed, they are potentially more likely to ‘step up’, wanting to avoid their classmates scoring them poorly. Perhaps include a chocolate prize for the highest scorers, too. For example:

Helping pupils to arrive at a rigorous enquiry question

As history teachers, we all know that designing enquiry questions is no mean feat. Michael Riley’s seminal Teaching History article on ‘Choosing and planting your enquiry questions’ serves as an excellent reminder about the importance of forming a rigorous question about history. Weak questions, such as ‘What was life like during the Vietnam War’ are merely descriptive. As Riley argues, “It does not take you into an understanding of the way history works.” The issue with weak enquiry questions is that “they encourage morally superficial or anachronistic judgements as opposed to historical thinking.” If the crafting of an enquiry question, which helps pupils to keep historical thinking about concepts such as causation, change and continuity, or evidence, at the forefront of their minds, whilst supporting the development of knowledge, is such a challenge for teachers, then surely it would be too prohibitive an exercise for students to engage in?

The 2013 National Curriculum History programme of study does not think it is prohibitive, and has high expectations that key stage three pupils can ‘”frame historically-valid questions”. Introducing pupils to the process of crafting a rigorous enquiry can help pupils to learn more about history as a form of knowledge.

How might I help make this difficult process accessible? This is what I decided to do.

- Help pupils to think about what makes a manageable enquiry question. This is a key principle that Sally Burnham introduced in her Teaching History article on ‘Getting Year 7 to set their own enquiry questions about the Islamic empire’. Introduce pupil to questions that are ‘too big’ to study, ‘too small’, and those that are ‘just right’. For example:

2. Ask pupils to think about what type of historical thinking is needed to answer different enquiry questions. Point out to them the importance of words such as ‘why’, ‘when’, ‘turning point’, ‘effect’ and ‘who’ in the crafting of enquiry questions on different historical concepts. Encourage them to recall when they have come across these types of questions before – ‘remember when we studied the causes of World War I?’…’remember when we asked ourselves who benefited from the industrial revolution?’…’remember when we decided what we thought was the most significant turning point of World War II?’ And so on. For example:

3. Provide a list of example questions on a different time period (so that they cannot copy) and then let them come up with their own question. It is vital that you then spend some time with the group REFINING the question, so that they don’t end up with a weak ‘what as life like?’

And finally…

Our independent learning scheme of work continues to be a work in progress. Yet, students in Year 11 have already commented on how much they enjoyed it, and how much they learnt about what it means to study independently. I’m not sure that they are quite ready for Simon Schama and his dancing red scarf, yet they have at least taken their first step (and, for some, their first step into the school library…).

References

Burnham, S. (2007). Getting Year 7 to set their own questions about the Islamic Empire, 600-1600. Teaching History 128 Beyond the Exam Edition.

DfE (2013). National curriculum in England: history programmes of study. London: HMSO.

Duffy, E. (2001). The Voices of Morebath: Reformation and Rebellion in an English Village. Yale University Press: New Haven.

Hammond, K. (2011). Pupil-led historical enquiry: what might this actually be? Teaching History 144 History for All Edition.

Riley, M. (2000). Into the Key Stage 3 history garden: choosing and planting your enquiry questions. Teaching History 99 Curriculum Planning Edition.